St Nicholas Church, built in the middle of the 14th century, is one of the oldest buildings in Brighton. It has also seen its share of some of our city’s most interesting women. In 1726 a baby called Martha Killick was christened here. She was later to find fame as Martha Gunn, the most successful of Brighton’s formidable bathing women who reigned supreme during the craze for wealthy Londoners, the Prince Regent among them, to take the fashionable sea water cure in Brighton. 89 years later Martha was buried right there in the churchyard in a shady plot that happens to be – appropriately for the ‘Queen of the Dippers’ – on one of the highest pieces of ground. Not far from Martha’s grave is that of the legendary Phoebe Hessel who, aged 15 and disguised as a man, ran away to join the army. Phoebe managed to lead a military career for 17 years until a bayonet wound revealed that she was a woman, leading to her services as a soldier being swiftly dispensed with. In more recent years, Flora Robson, one of the most iconic British actresses of the twentieth century, known locally as much for her charity work as her acting, spent the later years of her life at nearby Wykeham Terrace and was a regular member of the church’s congregation. I’d be surprised, however, if any visitor to St Nicholas Church, caused quite as much of a stir as a certain Sarah Forbes Bonetta, whose wedding ceremony was held here in August 1862. Sarah was as close to the heart of British upper-class society as it was possible to get, having been virtually adopted at an early age by Queen Victoria. But don’t let her typically English name fool you, because Sarah Forbes Bonetta was from Africa.

It’s thought that Sarah was born in 1843 in what is now southwest Nigeria of royal blood. Aged eight she was orphaned in inter-tribal warfare and captured by slave raiders. When she was found by Captain Frederick Forbes of the Royal Navy, she was a prisoner of King Gezo of Dahomey, who, according to American website http://www.blackpast.org was ‘the most notorious slave trading monarch in West Africa in the early 19th century.’ Captain Forbes had been sent to Dahomey by the British government in an attempt to persuade King Gezo to give up slave raiding and trading. When he came across the 6 year old Sarah – known as ‘Ina’ – he persuaded King Gezo to release her by suggesting that she would make an excellent ‘gift’ for Queen Victoria. ‘A present from the King of the Blacks to the Queen of the Whites’ was how he put it, thereby securing her rescue. Before setting sail for her new home, the girl was baptised Sarah and given Forbes’s surname, ‘Bonetta’ coming from the name of his ship. Forbes wrote in his diary that his young charge was a ‘perfect genius… far in advance of any white child of her age in aptness of learning, and strength of mind and affection…’ Sarah’s first meeting with Queen Victoria took place on November 9th, 1850 at Windsor Castle. She would have been aged about seven or eight. What on earth would such a young child, African born, and having spent the last couple of years of her life as a captive of slave traders, have made of suddenly being launched into the heart of regal pomp and power in England on a cold November day? Queen Victoria, who always took a shine to genuinely talented people, instantly liked Sarah, declaring herself impressed by her regal manner and intelligence. Following Captain Forbes’ death in 1851, the Queen entrusted Sarah to the care of a family in Gillingham, paid for her education, and regularly welcomed her at Windsor Castle where she delighted in her company and musical talent. When Sarah developed a cough a year later, concerned that the English climate wasn’t good for her health, she arranged for her to continue her education in Sierra Leone. In 1855, however, despite excelling academically, Sarah chose to return to Britain and the care of her unusual god-parent. In August 1862, not long after attending the wedding of Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter, the Princess Royal, Sarah was given permission to marry Captain James Pinson Labulo Davies, a 31-year-old Yoruba businessman from Sierra Leone who was based in London. There are a lot of websites telling Sarah’s story and many question whether ‘permission’ in this case would be better described as ‘pressure’ because it seems that, initially, Sarah’s interest in Captain Davies’ proposal was lukewarm. If she was as academically gifted as described, and having had the best education (for a woman at the time) that it was possible to have, it’s tempting to think that the life of a respectable and subservient Victorian wife wasn’t such an attractive destiny. Living through the dramatic events of her childhood and then being thrown into a completely different culture must have made her a resourceful and practical young woman. I wonder if she saw a more useful outlet for her remarkable skills? While deliberating on her choice she was sent to stay with a couple of older women in Clifton Street, Brighton. Whether this was a deliberate gesture to persuade the twenty-year old Sarah of the virtues of making a respectable marriage, the wedding went ahead. It must have been one of the most elaborate ceremonies ever seen in Brighton at the time. No less than ten horse-drawn carriages transported the wedding party, complete with sixteen bridesmaids, from West Hill Lodge to St Nicholas Church. The Brighton Gazette describes watching the procession of ‘White ladies with African gentlemen, and African ladies with White gentlemen’.

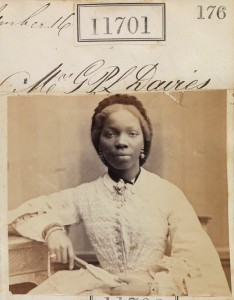

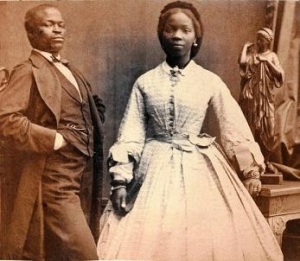

This photo of Sarah and her new husband was taken just a month after the wedding by French photographer, Camille Silvy, a popular photographer of the royal family, in his London studio. The couple went to live in Sierra Leone where Sarah worked as a teacher (hopefully finding a fulfilling outlet for her skills). Queen Victoria gave her permission to call her first daughter Victoria, and became her godmother. In 1867 Sarah returned to England with her young daughter and the Queen took immediately to her namesake, pledging to support her education. Sarah and her husband had two more children and moved to Lagos, Nigeria. Unfortunately, in 1880, while only in her late thirties, this talented and clever woman, whose life had been so eventful, succumbed to tuberculosis and died on the island of Madeira. Queen Victoria continued to support and take a real interest in the achievements of the young Victoria (below), who like her mother, was a talented musician and was a welcome visitor to the royal household for the rest of her life.

I have Brighton and Hove Black History to thank for reminding me of the story of Brighton’s African queen. I bumped into Bert Williams of Brighton and Hove Black History just the other day at the Museum’s War Stories Open Day. I’m always pleased to see Bert as he’s a treasure trove of local history. He’d brought along some really interesting panels that told the story of the 16,000 men, two-thirds from Jamaica, who came from the Caribbean to fight in the First World War, many forming the British West Indian Regiment in Seaford in 1915. Sarah Forbes Bonetta is one of the people featured on the Brighton and Hove Black History leaflet. To find out more about Brighton and Hove’s black history, go here http://www.black-history.org.uk/index.asp

Here’s another great link – 10 minute footage of Kamal Simpson talking to Clare Gittings, Learning Manager at the National Portrait Gallery, about Sarah. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4R3_Y0Rb1g