A few posts ago I bemoaned the lack of blue plaques for historical women in Brighton (less than a quarter of the city’s blue plaques commemorate women) One woman who does have a plaque, however, outside St John the Baptist’s Church in Brighton’s Kemp Town, is Maria Fitzherbert (1756 – 1837), pictured here by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Maria is remembered as George IV’s ‘secret wife’, ‘illegal wife’ or even – and this is very, very wrong – ‘mistress’. Has history been kind to Mrs Fitzherbert? After all, she’s not really remembered much for qualities or achievements of her own, but simply as a woman who earned her place in the historical hall of fame for capturing the eye of an important man. But Maria Fitzherbert, already twice widowed when she met George, the Prince of Wales, six years her junior in 1784, must have had something a bit different about her. In a large cast of mistresses, flirtations, dalliances, and infatuations, Maria’s is the name the Prince uttered under his breath when marrying his detested wife, Caroline of Brunswick. Maria is the person in whose favour he changed his will upon the birth of his daughter, Charlotte, and Maria’s miniature portrait is the one that was buried with him upon his death. The fickle, restless Prince seems to have been at his best, most generous, kind and well behaved when around Maria. Not only lover, secret wife and spouse, it was almost as if she was his good conscience, a sort of living reminder of all the things he could be if only he tried, the key to access his better self.

When Viva Brighton magazine asked me whether they could interview me about Maria Fitzherbert earlier this year for their February issue I started thinking more about what sort of person she was and the nature of the mysterious hold she had over this powerful man. This is a slightly abridged version of the article from Viva Brighton by Steve Ramsey (March 2015) Image below Maria Fitzherbert after Richard Cosway, 1792.

“He lied to her and cheated on her and was sometimes cruel. He dumped her twice for other women. He was not above using suicide threats to win her, or to win her back. He coaxed her into a secret wedding, then humiliated her by getting a friend to publicly deny it had happened. He repeated the humiliation by marrying again, as if she had merely been his mistress. Yet she was clearly the love of his life, and he risked the throne to be with her. And she seems to have loved him too. It was, as one book on Mrs Fitzherbert points out, ‘a very strange love story’.

“He was brought up strictly, with a relentless and harsh education regime that included being flogged if he made mistakes in Latin grammar,” Royal Pavilion guide Louise Peskett says. “That’s what his father thought would make his sons into good upstanding men. But, if we look at his upbringing through 21st-century eyes, we could see him as an abused child who had a very remote relationship with his parents.

“And, sure enough, he became a person who couldn’t control his impulses very well, who developed problems with addiction. These days, it would be ringing alarm bells; we’d say ‘that’s a person with problems’.”

Prince George was reckless with money, impulsive, melodramatic, and sometimes selfish. But he was also intelligent, witty, charming and sociable. Tall and handsome in his youth, he had a series of lovers, all of whom were content to be mistresses. Maria Fitzherbert wasn’t.

She was six years older than him, a convent-educated Catholic who’d been widowed twice before they met. She liked dancing and music, and had a ‘lively’ sense of humour, biographer James Munson notes, but was also a ‘woman of considerable pride,’ who cared strongly about propriety and respectability. It was marriage or nothing.

By law, no-one married to a Catholic could succeed to the throne, and Prince George was first in line. This should have put him off, but, after they met in March 1784, he began a reckless and relentless courtship. She planned to go to Europe to avoid his attentions; when he heard this, he ‘stabbed himself and made out that it was a suicide attempt,’ biographer Saul David notes.

She went to Europe anyway. George ‘cried by the hour,’ according to a contemporary account, ‘rolling on the floor, striking his forehead, tearing his hair, falling into hysterics…’ He wrote her frequent, passionate letters, sometimes threatening suicide. She resisted for more than a year.

“I’d have thought if you fake suicide and batter someone with letters and send messengers all over Europe for them…” Peskett says, “and they don’t respond, you’d think, after a couple of months, he would have thought ‘oh, ok then, never mind’. She must have really meant a lot to him.

“I’m sure she genuinely did like him, but her feet were on the ground. She was older and more practical, she could see the bigger picture and the problems it could cause, and put her good sense before her heart.”

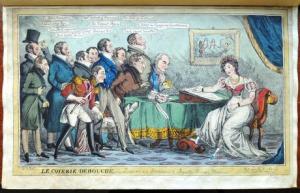

Nonetheless, they married in December 1785 in secret. Their relationship status became a popular subject of gossip. The prince manipulated his friend, the MP Charles Fox, to deny the marriage in parliament; George then went to Mrs Fitzherbert and claimed to be astonished at what Fox had said. A witness claimed: ‘Maria turned very pale, and made no reply.’ She refused to see George for some time, which made him so distressed that his health suffered.

After she took him back, they went to Brighton for the summer of 1786, where they were ‘a picture of romantic contentment,’ according to a magazine called Royal Romances. ‘In those brief but happy months, the prince appeared to be a reformed character. He drank only moderately, gambled hardly at all, and entertained quietly.’

In the next few years, they spent a lot of time together in Brighton. “It was one of the places they escaped to,” Peskett says, “where they could have a taste of domestic bliss, and enjoy each other’s company like an ordinary married couple.”

(Image above of the Marine Pavilion, the predecessor of Brighton’s Royal Pavilion built by Henry Holland in 1786 where Maria and the Prince spent their time in Brighton).

However, things were going less well by late 1793, Saul David notes. She had ‘long disapproved of his dissolute lifestyle and disreputable friends’. He was so extravagant that she ‘often had to lend him money’. By 1794 the brilliant and ruthless Lady Jersey had elbowed her way into the Prince’s affections. As his mistress, she set about poisoning his mind about Maria, convincing him ‘that his unpopularity with the people was due to Mrs Fitzherbert and her religion,’ biographer Valerie Irvine writes. ‘She also told him that Maria had been heard to say she was only interested in his rank, not in his person.’ In June 1794, the prince dumped his wife by letter.

By this point, George’s debts were enormous, and ‘in return for financial help, the king insisted that he should marry a Protestant princess,’ the Dictionary of British History notes. So, in 1795, he wed his cousin Caroline of Brunswick, who he loathed at first sight. They separated the following year.

After another series of ‘increasingly desperate’ overtures, Mrs Fitzherbert took him back around 1800, Saul David notes. She had been looking after a child called Minney Seymour, and “it sounds like they had a few happy years, playing parents with this little girl,” Peskett says. The Prince was certainly very fond of her.”

When Minney’s parents died, there was a custody battle between her family and Mrs Fitzherbert, who was devoted to the child. Minney’s relatives Lord and Lady Hertford helped Maria; they became the child’s legal guardians, and let Mrs Fitzherbert keep her.

Maria was very grateful, but then Lady Hertford became the Prince’s latest mistress, and “used her influence on George to widen the gap between them,” Peskett says. “After this latest set-back their relationship sort of limped on, but without the passion of previously.”

To keep her own affair secret, Lady Hertford forced Mrs Fitzherbert to play the dutiful wife at social events, threatening to take Minney away if she didn’t. Maria told the prince his latest fling had ‘quite destroyed the entire comfort and happiness of both our lives’.

The final breakup came in June 1811, a few months after George had been made Prince Regent. Having been invited to a fete at George’s London residence, Mrs Fitzherbert was told she wouldn’t be seated near the Prince. “That’s how he let it be known to her that she was dispensed with,” Peskett says.

“This followed the pattern of their first break-up, when after responding to a letter that began ‘My dearest Love’, requesting her presence in London, Maria dutifully turned up only to be given another letter announcing that he didn’t want to see her again. It makes you wonder how confused he was in his own mind about it, and how easy he was to sway.

“He was very mercurial and led by his heart… Whereas she seems to have been quite calm and had her with both feet on the ground,” Peskett says. “I think she was a kind of safe harbour for the tumultuous waves of his personality, as it were. George’s mother, during one of their ruptures, even wrote to her and asked her to make it up with him, because his behaviour was so bad without her as a steadying influence.

“I think she was very strong and stoic. But how must she have felt? To be rejected for other women, and the blowing-hot-and-cold in their relationship. And, from the time he lied to her about Fox’s statement having nothing to do with him, she must have known that she couldn’t really trust him, despite these violent protestations of love. That must have really been difficult. But, of course, she would have been aware what was at stake for him, what he was risking… So that helps us to understand his point of view as well.”

After 1811, they wrote to each other ‘occasionally, but their letters were confined to practical matters, usually money,’ according to Royal Romances. She Maria lived mainly in Brighton from about 1815, and if she met the King there, they would ‘exchange frosty glances’. It’s frequently said that the people of Brighton were very fond of Maria, and this has been suggested as one reason that George’s later trips to Brighton were mostly spent in seclusion in the Pavilion.

Before George died, in 1830, he ensured that he would be buried with a locket containing a picture of her. When told of this gesture, Maria was seen to be crying.

After the interview I started to think how Maria Fitzherbert’s life could almost be the template of a Hollywood rom-com or a work of romantic fiction. Lone woman with sad past wooed by roguish but attractive alpha male who promises her the world. Then, when alpha male lets her down, refuses to crumble, creating instead a better life for herself built on strong principles, strength of character and the fact that she’s made a lot of friends and gained respect along the way. Lives happily ever after. When George IV died in 1830, Maria had already created a supportive bubble of family and extended family, based largely on her two adopted daughters. Perhaps there’s some kind of justice that, years after the death of her secret royal husband, Maria still enjoyed the Royal Pavilion as a guest of William IV and Queen Adelaide.

St John the Baptist’s Church, Bristol Road, Brighton. Resting place of Maria Fitzherbert.