by Herbert Rose Barraud, published by Eglington & Co, carbon print, published 1889

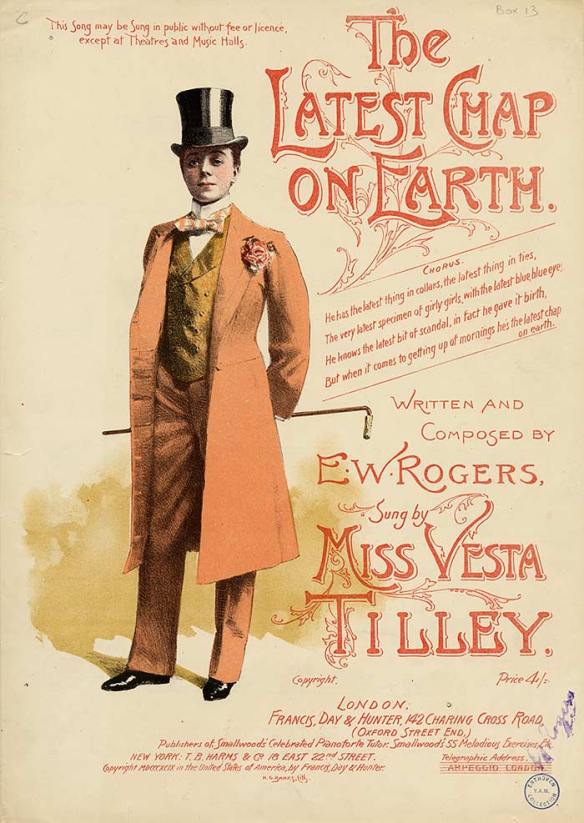

One week to go before my first ‘Notorious Women of Hove’ walk and I’m still marvelling at the incredible number of Hove related women who’ve made their mark on the world. Given that I’m supposed to be planning a nice one and a half hour amble rather than a full day’s trek, I’m having to make hard decisions about which of the pioneering doctors, surgeons, educators, suffragettes, poets, singers, social campaigners and plain, old-fashioned trouble-reapers to include and which I can only give a cursory mention to? One woman I definitely want to tell people about is Alice Ann Cornwell (above) who came to live in Palmeira Square in the early 1900s. Hardly a house-hold name, Alice’s list of achievements is impressive: industrialist, gold-miner, entrepreneur, newspaper proprietor and, ultimately, the originator of the Ladies Kennel Association.

Born in Essex in 1852, Alice spent most of her childhood and teenage years in New Zealand. She returned to England in 1877 and showed great promise as a musician, training at the Royal Academy of Music and composing music and songs. Finding out that her father, now a gold prospector in Australia, was in financial trouble, however, she abandoned her music career in order to help him. Once back in Australia, Alice took a practical course of action: she decided to study geology and mining. Unafraid to get her hands dirty, Alice often rolled up her sleeves up and got involved in the hard and dirty work of mining itself. Women weren’t as rare in the mid to late nineteenth century Australian goldfields as you might imagine. The 1854 census of the Ballarat goldfields in Victoria, where Alice worked, revealed 4,023 women compared to 12,660 men living on the ‘diggings’, with five percent of them single.

Whether these women were wives of miners or mining themselves, it was far from being an easy life. Intensely hot summers, freezing cold winters, lawlessness, little, if any, infrastructure or facilities, the remoteness and lack of transport meant that in some of these communities minor illness or pregnancy could be death sentences. A woman by the name of Ellen Clacy wrote these vivid observations of life on the Victoria goldfields in 1852: “Night at the diggings is the characteristic time: murder here-murder there- revolvers cracking-blunderbusses bombing-rifles going off-balls whistling-one man groaning with a broken leg…..Here is one man grumbling because he brought his wife with him, another ditto because he left his behind, or sold her for an ounce of gold or a bottle of rum. […] In the rainy season, he must not murmur if compelled to work up to his knees in water, and sleep on the wet ground, without a fire, in the pouring rain, and perhaps no shelter above him more waterproof than a blanket or a gum tree…..In the summer, he must work hard under a burning sun, tortured by the mosquito and the little stinging March flies…..” Despite these hardships, Alice worked hard and struck gold. So much gold that soon she was able not only to sort out her father’s hardships but make an excellent living for herself too. With her business-mind swinging into action, Alice quickly established a company that was floated on the London Stock Exchange. Fantastically wealthy, shrewd, and with a big personality to match, Alice was soon a celebrity, dubbed the ‘Lady of the Nuggets’, even, in 1888, inspiring a novel, ‘Madame Midas’ by Fergus Hume.

Back in London with her fortune, Alice turned her mind to other business opportunities. In 1887 she bought the ailing Sunday Times and, installing her fiance, Frederick Stannard Robinson, as editor, managed to quadruple circulation. In 1894 she founded the Ladies Kennel Club. This organisation, still going strong today, describes Alice as ‘formidable’ on their website. She set up the organisation ‘in defiance of the gentlemen of the Kennel Club of the day’ with the aim to put on dog shows ‘run by Ladies for Ladies’. Unusual for the day, its offices were staffed entirely by women. Cats got a look in too, as Alice later became involved with the National Cat Club, as well as the International Kennel Club. Widowed in 1902, Alice settled in Hove where she bred pugs until her death in 1932. Despite making huge strides in worlds only sparsely populated by women, a New Zealand newspaper, the Otago Witness, chose to focus more on her looks in an 1889 profile: ‘Miss Cornwell is, if not a prepossessing woman, at least not unhandsome. Her face and features somewhat irregular and undefined, it is true, harmonise well with her symmetrical and well defined picture.‘ I’d like to think that ‘formidable’ Alice Cornwell was too busy to let this bother her.

Notorious Women of Hove – guided walk during the Brighton Fringe Saturdays 30th April, 7th May, 14th May, 28th May, 4th June at 10.30 a.m from the café in St Ann’s Well Gardens, Hove. Thursday evening 12th May, Tuesday evenings 17th May, 31st May at 6.30 p.m from the same place.