Some days I really love my job.

My mission on Saturday 13th September: take the 15th Ludhiana Sikh regiment on a tour of the Royal Pavilion. It wasn’t supposed to work out like that. I’d been hired to be Brighton Museum’s French speaking meet and greet for its War Stories Open Day, a real pic n mix of an event where visitors could research their First World War ancestors, listen to poetry and prose inspired by the conflict, hear wartime songs, rub shoulders with costumed characters, have a suffragette explain to you just why women should be given the vote, get close to military uniforms and kit, and generally find out more about how the years 1914 – 18 were experienced by the people of Brighton. With the hordes of French visitors conspicuous by their absence, however, and my paper Tricolor quickly wilting, it was decided to find a better use of my time. And what better use… The gentlemen in question, although looking as if they’d just stepped out of a time machine from 1914, were from the National Army Museum, part of a living history project in conjunction with the Anglo-Sikh Heritage Trail called ‘War and Sikhs: Road to the Trenches’ ‘http://www.nam.ac.uk/microsites/future/join-in/nam-about-town-country/war-sikhs/ . Made up of volunteers and staff from the National Army Museum, its aim is to ‘bring the Sikh military story to life’ by recreating a formation of soldiers from the 15th Ludhiana Sikh Regiment as they would have appeared on the battlefields of the First World War. This contemporary postcard shows them arriving in France…

(Note the caption in French and English… ‘Gentlemen of India, marching to chasten German hooligans’.) I’ve mentioned on this blog before that 1.3 million Indians fought in the First World War, 20% of them Sikh. The Brighton connection, of course, is that the Royal Pavilion Estate, as well as other premises in the city, became military hospitals for the wounded. Here’s a picture from the Royal Pavilion and Museum’s tumblr ‘A War Story A Day from Brighton Museums’ http://brightonmuseums-ww1-war-stories.tumblr.com/ of our ‘soldiers’ being greeted by the Mayor in the Dome…

As I crossed the gardens from the Museum to the Royal Pavilion with the ‘gentlemen in khaki’ as the local newspapers were fond of calling them, I felt more like a celebrity minder. Camera phones clicked, flashbulbs popped, heads turned and jaws dropped as we made our inevitably slow progress across the few metres of path. It’s not every day, after all, that you see a regiment of Indian soldiers in full battle dress among the buskers, EFL students and sunbathers who throng this part of town on a sunny afternoon. ‘Uncanny’ was how I’d describe giving a guided tour to these very special visitors. For years I’ve done talks and tours about the use of the Royal Pavilion as a military hospital and I’ve spent hours poring over old black and white photos of Indian patients recovering in the gardens, sitting in beds in the Banqueting Room, posing in regimented lines on the lawns. To suddenly have these photos come to life, the characters from them slipping out of the frames and walking around, asking questions and patiently listening to me tell them about George IV and how many crystals are in the Banqueting Room chandelier, was one of the oddest experiences of my working life. (‘Uncanny’ is probably the word they’d use for my guiding style too… Lots of ‘ums’ and ‘ers’ as I tried to remember whether I’d fallen down some kind of rabbit hole, Alice in Wonderland-style, and been transported back one hundred years.) The spell was only broken when in the Music Room we happened upon a bride and groom posing for wedding photos and one of the ‘soldiers’ cheekily observed what a great photo-bombing opportunity we had. (We didn’t. Although the bride and groom didn’t look as if they’d have minded if we had). After having a look round the ground floor and sharing some of the inevitable Royal Pavilion wow moments, we went upstairs to spend some time in the Indian Military Hospital exhibition gallery where we all stood watching the crackly and silent 1915 film footage of George V and Queen Mary presenting medals to some of the injured soldiers in August of that year, one of them being Sebadar Mir Das, awarded the Victoria Cross for his courage at the second Battle of Ypres. We made the discovery that the displayed souvenir book produced by the military authorities in 1914/15 for the patients featured a soldier from none other than the 15th Ludhiana Sikh regiment on the cover.

For one of the volunteers, Kuljit Singh Sahota, bringing this part of the past to life had a particularly personal significance. His great great grandfather was Manta Singh, a member of the (real) 15th Ludhiana Sikhs, who was fatally injured while wheeling a fellow soldier to safety in a wheelbarrow during the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, and whose story is featured in the Museum’s current War Stories exhibition. Read more about Manta Singh here http://www.cwgc.org/foreverindia/stories/manta-singh-neuve-chapelle.php. Then it was outside once more for interviews, photos and filming. Celebrity minding time again. The people of Brighton, not known for their shyness, quickly mobilised around us. ‘Who are you?’ ‘What are you doing?’ ‘Wow, they look fierce! I wouldn’t like to get on the wrong side of them.’ Hands were shaken, backs patted, and selfies with an Indian soldier became the hottest ticket in town. Ahem.

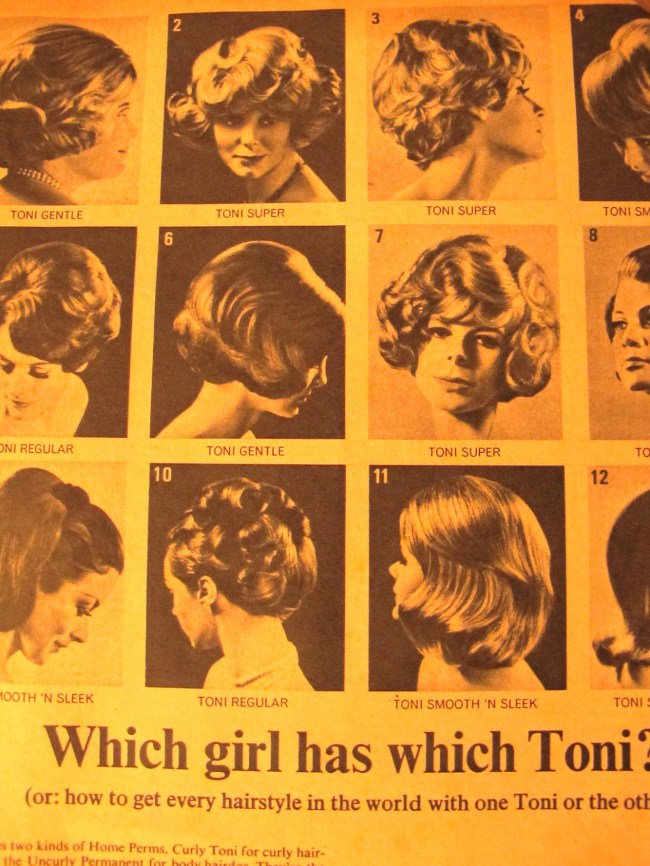

‘This might take some time,’ I thought as a coachload of Italian teenagers passing through the gardens suddenly congregated around us and a man with green hair and a Sex Pistols T-shirt took it upon himself to start relating the story of the Royal Pavilion’s past as a military hospital to passers by, soon ending up with a crowd around him. ‘What’s going on?’ some French tourists (arriving late for my meet and greet, no doubt) were heard to ask. ‘It’s sort of street theatre and public lecture all at the same time,’ someone suggested. I couldn’t help noticing that some of the people who were asking questions and chatting to us were definitely not going or coming back from the Museum’s War Stories Open Day. What a great example of how props, costumes and living history can reach out to the places museum exhibitions can’t. Impromptu Q and A sessions abounded. One of the things that I found out about was the point of ‘putees’, i.e. the thin strips of cloth worn tightly around the lower leg, like these…

When tied with sufficient tightness, they strengthened the leg and helped support the considerable weight of the equipment that had to be carried. And no, contrary to appearances, they don’t get soggy in the rain. Made of very finely knitted wool, they protected the lower leg from moisture, would dry easily, and stopped boots disappearing into mud. As the afternoon drew to a close and evening fell, it was time for some last photos on the east lawns in front of the building before the party finished their day at the Chattri (the site on the South Downs where the Hindu and Sikh soldiers who lost their lives in the Brighton hospitals were cremated, now marked by a white marble memorial,) As the sun went down and a hazy sepia tinted light fell, the 15th Ludhiana Sikhs lined up for a very formal, straight-backed, military portrait. It was easy, again, to forget we were in the twenty-first century …Until a local man, caught napping in the grass in front of them suddenly woke up. ‘Oops, sorry, do you want me to move, mate?’ ‘That’s OK, one of the Indian soldiers called across. ‘We can photoshop you out.’ I learnt a lot that day, not least about how far costumes, props and simply getting out and about and talking to people can make history approachable and user-friendly. Thanks to the 15th Ludhiana Sikhs for their company and sharing their knowledge, as well as for providing possibly the most surreal moments of my career. (And working in museums, there’s a lot of competition for those.) I will be leading guided First World War estate tours across the Royal Pavilion Estate – and probably won’t be able to stop myself from talking about this – on October 18th, November 8th and December 27th starting at 10.30. I’ll be joined in guiding duties by my colleague, Paula Wrightson, and one of the Dome’s brilliant event managers who will take us behind the scenes in the Dome and Corn Exchange to explore further how these buildings were used during the war. For information, 03000 290900.

Thanks for bearing with me with this post and its lack of historical Brighton women, by the way. Many, many more of our fantastic local women to follow shortly…